I came from a software delivery world, and I mean that very literally. Wind back the clock not even 10 years and SaaS was an outlier, not the mainstream. Software developers were responsible for shipping software (even the term shipping has connotations of that being the act that delivers value to customers rather the just the first step). In the world of software delivery efficiency, time is valued when it is spent working on features. Which begs the question, what happens when a team now has the added task of running services; and what does that even mean or entail?

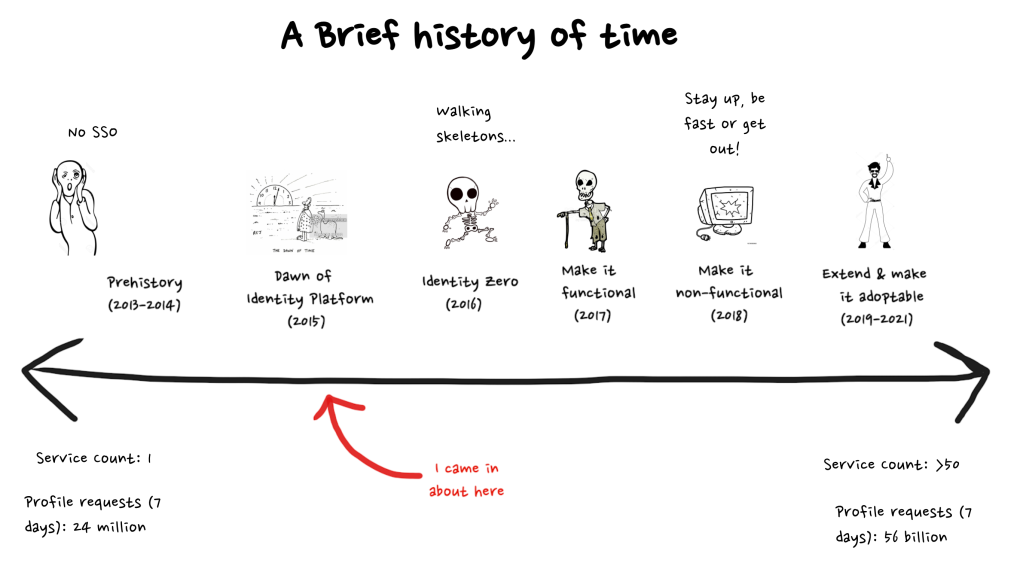

My journey in DevOps started around 2016. At the time we had an SRE team for Atlassian account and we had operations folks that looked after our VM-Per-Customer offering. We had just started launching services and had settled on You-Built-It-You-Run-It as our operating model; but how would software engineers make the transition? Luckily, we had a couple of tail winds that helped us make the transition. Firstly, Identity started out as a platform that was mostly a system of record; users, groups, access was configured in Identity but it was then synced out to the products who dealt with the gnarly runtime requirements. This meant that we didn’t have a large volume of requests or low latency or even high reliability. Secondly we had evolutionary pressure from a new product being developed – Stride (HipChats to-be-but-not-quite successor). Stride didn’t want to (nor had the time) to build all the non-differentiating stuff. At the same time they had a strong engineering lead who early on established the measure of operational success – “Can I F$#ken chat?” and a weekly spark line showing where they weren’t able to and who was responsible.

I was trying to figure out – how am I going to justify to myself or anyone else the investment that is going to be required for teams to know what is going on in prod, figure out how to fix it and prioritise it amongst all the stuff we have to build and ship? I remember a discussion with the SRE lead in Identity at the time and in a very simple sentence he gave me something that has stuck with me every since…

If you want to be good at something you need to spend time on it.

I’m going to labour the point here a bit so indulge me. The reason this statement is so powerful is that:

- its simplicity – never underestimate the power of a concise message that short enough and powerful enough to be repeated by others.

- I’m not telling you what needs to be done. It is a question with an obvious logical consequence you can’t argue with. The reality is self evident; we need to be good at operations, that teams (not just individuals) need to spend the time to grow that muscle and learn to become good at it.

Great we’ve got the time, so now what do we spend it on?

People often don’t realise it but engineering leaders still build systems; they just extend out beyond software. We work in a repository of people, tools and processes. One of the engineering disciplines that has influenced how I think about steering teams toward success is control theory; thinking of the desired output of a system and the role of feedback in driving it toward that state. In this case by asking teams to meet, to look at their key operational data and determine corrective action in a weekly meeting that is known as TechOps. The outcomes are presented to leadership and teams held accountable in TechOps rollup (held the day after). The ritual came from Stride but like all good engineering processes it is basically an implementation of the inspect and adapt feedback loop with leadership choosing the things that are of value and the weekly presentation providing bidirectional feedback on if we’re moving in the right direction.

Alright, but what should teams be looking at? What is “key operational data”? The answer is it is something that evolves and what things teams focus on and how many is a key way leaders drive those changes and the evolution of your operational maturity. Ours was quite simple:

- Incidents in the past week – what incidents did we have, why, what are we doing about it

- Alerts – how many have we had, are they signal or noise? If they’re signal what action do we take to automate addressing the problem.

- Service SLOs – did we meet or miss / why and what are we doing?

- Overall what are the trends? We care less about an errant week than an ongoing or emerging problem.

Why these? At the beginning we didn’t have great telemetry. We had service level SLOs (like how many 9s of 2XX vs 5XX HTTP responses you had) but that didn’t really correlate with customer impact (Incidents). High quality alerting is critical – if signal-to-noise is poor alerts are ignored, if you have none you’re entirely dependent on customers to tell you there is a problem or engineers noticing something is going wrong (the quality of your automated detection is absolutely key). Which brings me to another philosophical maxim…

If you have $10 to spend on reliability, spend $8 on your observability

This is heavily predicated on “If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it”. You can pour a lot of concrete to solve a problem you don’t have or leave a lot of problems unanswered if you don’t have good eyes on what customers are experiencing in Production. In the absence of good observability you are relegating your customers to being detectors. In case it is not apparent, customers do not like this and are the one form of detector that can self elect to remove themselves from your observability suite. They are however the most accurate detector and you will fall back on them from time to time, so do yourself and them a favour – make this a rare occurrence.

So what kind of measures should you have?

- service quality – did the system deliver the experience expected to customers aka. “Can I f@#king chat”.

- early warning signals – measures inside the system that are a prelude to a problem occurring – heaps size, CPU, latency, queue length; i.e. technical measures that correlate to the system behaving correctly but can’t actually tell you if customers are getting what they want. They can however tell you when there is a problem brewing that may soon result in a service quality issue.

Why have both? Why not just measure service quality and be done with it? In an ideal world if you can resolve your performance to customers down to whether your end point returned 2XX then you are living the dream. This is a great first step on your DevOps maturity but what was the payload in that response? Did it contain the expected information (i.e. is the system up but wrong)? Your API may be working but is the single page App that sits atop it behaving? Resolving answers to those questions can be complex. For Identity one of our service quality metrics is “Can I F@#ken login?” Login is a multi-step flow depending on if you are using username/password, SAML, is 2FA enabled? Did I need to reset a password? Did a user go and grab a coffee part way through that flow? We are more tolerant if 1/1000 logins failed but could immediately retry and succeed (i.e. the failure is not persistent). Hence we can’t immediately tell if login is falling below our internal SLO of 99.99% because you need to track users from start to finish and we allow up to 5 minutes for a user to do that before saying “if a user didn’t login and we saw an error of some kind we will treat that as a failure”.

The other reason teams don’t think about is…

Your uptime is part of your marketing collateral

Atlassian is a federation of products, new acquisitions are made, new products are built. Atlassian serves everyone from 10 member startups to the fortune 500. One of the big impediments of moving to cloud are concerns on reliability. Hence, one of the biggest worries for those customers (and the products looking to come aboard your platform that serve those customers) is your uptime. Having a 12+ month trend of meaningful service quality metrics goes a long way to built trust and transparency.

In case you don’t already have your number-of-nines times tables memorised; 99.99% across a month only allows 4 minutes of downtime before breaching. Service quality measures by definition only tell you once you start to negatively impact the customer experience and can have too much lag to be your primary means of detection / automated rollback. Early warning signals give you faster feedback that is less precise but faster to respond to; hence you need both in balance.

Signal to noise ratio is king

My last piece of advice for this post is that If I said invest $8 on observability, spend half of that on ensuring you dial signal to noise up to 11. It shouldn’t really cost you that, but in terms of priorities that is where I’d set them. Folks say noisy alerts wake people up at night, this is true. But any alert that fires on a regular basis because of some expected but un-actionable phenomena creates a noise floor that masks real problems slowing MTTR (in some cases by many hours / overnight) because the team thought it was the “everything is as expected alert”. They can also hide paper cuts and bugs that might not be major incidents but may present low hanging opportunities for the team to improve.

Do not overlook signal to noise in logs. We specify a standard on how logging levels should be used:

- Error – Something that should never happen and if it does warrants investigating – e.g. a service responded with a 409 when we only ever expect it to respond with a 200, 401 or 5XX. If this happens you should fire a high priority alert because something is up. You should expect to see Zero errors.

- Warning – Things that go bump in the night but are anticipated – e.g. a failed call to a dependency, you’d log as a warning, you may choose to alert on these if you see high volume in a short window. You may see many of these in a week for a high volume service and you should investigate if you are seeing a number of these or an upward trend.

- Info – BAU logging and operations. E.g. used for access logging for people looking to investigate things

The best teams I’ve seen actively review their alerts and logging during standup to talk about whats going on in the system and filter through work to drive those numbers down. Having consistency and clarity on what logging levels equate to what level of response and using it to drive investigation and fixes of underlying problems is a great way to ensure a fast response when there is a major problem as well as ensuring overtime you address the paper cuts that can add up. It also removes tribal knowledge on what alerts/logs “are ok/expected” vs those that “might be bad” – the level and trends tell you.

So where are we now?

On the day TechOps was announced, our SRE lead presented at the town hall and asked everyone in the room to put their hand up if they knew the SLO of the services they ran. In a room of ~50 people I think I saw maybe 4 hands go up.

Today every team runs TechOps on a weekly basis and we do a rollup. Identity is seen as a leader inside Atlassian when it comes to operations and reliability. We now focus on other metrics beyond service hygiene and health we talk about:

- Security Vulnerabilities and approaching SLA breaches to ensure we patch high CVSS issues promptly

- Support escalations and SLAs to ensure teams are acting on support asks with urgency

- Cost and wastage – we look at our AWS spend trends and obvious opportunities to reduce waste

- Service Quality metrics where we’re in breach or we’ve burnt more than 20% of our error budget – we now have enough confidence in teams to look at their own early warning signs and signal to noise in observability that what we focus on is accountability and action on quality measures.

We have a quarterly operations review where we look at overall trends, proactive reliability initiatives to make systems ever more resilient and compartmentalised in their blast radius when things go wrong. We have a quarterly FinOps review to project costs for the coming quarters and consider opportunities to change the system to make it more cost efficient. Are we done yet? No… DevOps is a journey and is as much about building knowledge and a culture in teams as it is about the resulting services that get run. Even with a platform thats globally distributed serving >10^10 requests a week, we are all still learning.

Thanks for reading, as usual, keen to hear your thoughts / experiences and feedback.